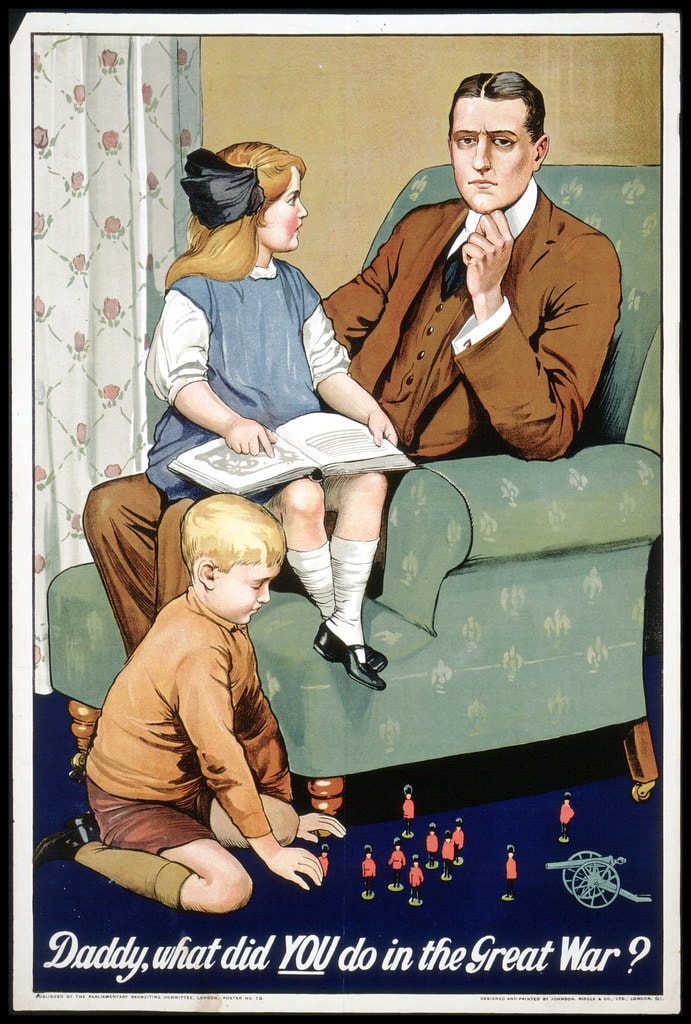

You probably know this poster. A besuited father sits in an armchair, his daughter on his lap. At his feet, his son plays with toy soldiers. It is a picture of domesticity – but the father looks troubled, as well he might, at the thought that one day his children will hold him accountable for his choices.

There were many posters such as this, but this is the one that has stuck, no doubt because of the powerful emotional tug-of-war between the domestic hearth and the father’s higher duty. A bit like ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’, it has been parodied and pilloried over the decades since.

But perhaps there’s a question for us all. What did you do in the pandemic? Did you learn to bake? Did you take up crafting or perfect your French? Did you become a street champion or food bank volunteer? Did you simply struggle to keep your head above water? What will we tell our children and grandchildren about this extraordinary chapter in our lives?

One of the most striking things about the first lockdown in March 2020 was how sharply people’s lives divided. For everyone who was furloughed – or worse, lost their job – there was someone else working doubly hard simply to hang onto their employment, or because their industry demanded (repeated) reinvention for pandemic times. It was sink or swim. And if you were putting in the extra hours, there was little more irritating than endless Instagram posts of the perfect sour dough loaf or the Marie Kondo airing cupboard.

It is said that literary agents have been swamped with novels since the start of the pandemic. Lots of people had time on their hands. Some were being paid to stay at home and do nothing. What better opportunity to write that book they’d always meant to? That’s the story, anyway. And yet, and yet… I do wonder if this holds water. Are there really enough people out there with both the desire and the grit to stick with the project to make a measurable difference to agents’ in trays?

Maybe. My doubts are these. First, writing a novel is very hard work. (I would say that, wouldn’t I? why would I want anyone to think it was easy?) It requires a complex balance of skills in plotting and researching and writing and editing. Inspiration is the easy bit: the tough part is the perspiration, as the saying goes. Having the self-discipline to stick with it, to see it through. Or course I may be quite wrong … but while I can well imagine plenty of would-be writers setting out, I wonder how many actually got to the end?

The other reason I have my doubts is related to the sheer isolation of lockdown. Three months on your own may sound like the introvert’s dream. And up to a point, I’d agree. For many people having the time and space to write is an extraordinary gift. A privilege. Even if we assume for a minute you weren’t distracted by home schooling or money worries or fear of losing your job or anxiety about a loved one contracting the virus (and most of us fell into at least one of those categories, surely) there’s another fly in the ointment. It’s hugely challenging to write without human interaction.

Where do you get your ideas? I’m sometimes asked. And the answer is that they are everywhere around you. You might have a spark of an idea but you need to do some research. You need libraries or visits to places. You need to survey the scene. Walk the landscape. Test your ideas, check your facts. You need to overhear that conversation on the bus that makes you think, Ah, yes… You need that supper with friends that somehow nudges you over a sticky plot point, even without a word spoken about the blockage. In short, you almost certainly need stimulation beyond the recesses of your own brain.

The creative process is an extraordinary one. Sometimes it’s plodding. Often it’s frustrating. On good days you sit down to write and the story flows. Ideas you didn’t know you’d been thinking about pour onto the page. Hooray for the subconscious mind which works away at a story when you think you’re off duty. Walking, talking, sleeping even. If I’ve learned anything over the course of writing my three published novels it’s that I need to write a plan, to show up at the page and then just get on with it. Without worrying too much.

I recently heard the handbag designer Anya Hindmarch talking on the radio about her creative process. ‘It’s quite difficult with all the museums and exhibitions shut at the moment,’ she said. ‘I need to keep things going in.’ Her solution? She ‘banks’ ideas when she gets the chance, and goes back and ‘grazes’ on them later.

That was a lightbulb moment for me. I suddenly realised why the pandemic has been such hard work for me as a writer. Yes, some of us have the unaccustomed luxury of time. But let’s face it, life under lockdown has been pretty boring, even setting aside for a moment what a wise friend of mine calls the ‘ambient anxiety’ brought on by the pandemic. You’ve probably noticed in your conversations with friends. We haven’t got anything to bring to the table because none of us has done anything very interesting.

‘Surrounding myself with images I find interesting or inspiring subconsciously prompts ideas,’ said Anya Hindmarch. ‘That and a glass of wine. It relaxes me and the creative juices begin to flow.’

So yes, I’ve written a novel during the pandemic. Or finished and edited one that I’d already started. Joy and Felicity is officially launched. I haven’t started anything else concrete, although I’ll confess to playing with some early ideas for what may turn into my next book. Nor have I made ten types of sourdough, taken over an allotment or improved my French. But I refuse to beat myself up about that. Sometimes simply keeping afloat is enough of an achievement.

There were many posters such as this, but this is the one that has stuck, no doubt because of the powerful emotional tug-of-war between the domestic hearth and the father’s higher duty. A bit like ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’, it has been parodied and pilloried over the decades since.

But perhaps there’s a question for us all. What did you do in the pandemic? Did you learn to bake? Did you take up crafting or perfect your French? Did you become a street champion or food bank volunteer? Did you simply struggle to keep your head above water? What will we tell our children and grandchildren about this extraordinary chapter in our lives?

One of the most striking things about the first lockdown in March 2020 was how sharply people’s lives divided. For everyone who was furloughed – or worse, lost their job – there was someone else working doubly hard simply to hang onto their employment, or because their industry demanded (repeated) reinvention for pandemic times. It was sink or swim. And if you were putting in the extra hours, there was little more irritating than endless Instagram posts of the perfect sour dough loaf or the Marie Kondo airing cupboard.

It is said that literary agents have been swamped with novels since the start of the pandemic. Lots of people had time on their hands. Some were being paid to stay at home and do nothing. What better opportunity to write that book they’d always meant to? That’s the story, anyway. And yet, and yet… I do wonder if this holds water. Are there really enough people out there with both the desire and the grit to stick with the project to make a measurable difference to agents’ in trays?

Maybe. My doubts are these. First, writing a novel is very hard work. (I would say that, wouldn’t I? why would I want anyone to think it was easy?) It requires a complex balance of skills in plotting and researching and writing and editing. Inspiration is the easy bit: the tough part is the perspiration, as the saying goes. Having the self-discipline to stick with it, to see it through. Or course I may be quite wrong … but while I can well imagine plenty of would-be writers setting out, I wonder how many actually got to the end?

The other reason I have my doubts is related to the sheer isolation of lockdown. Three months on your own may sound like the introvert’s dream. And up to a point, I’d agree. For many people having the time and space to write is an extraordinary gift. A privilege. Even if we assume for a minute you weren’t distracted by home schooling or money worries or fear of losing your job or anxiety about a loved one contracting the virus (and most of us fell into at least one of those categories, surely) there’s another fly in the ointment. It’s hugely challenging to write without human interaction.

Where do you get your ideas? I’m sometimes asked. And the answer is that they are everywhere around you. You might have a spark of an idea but you need to do some research. You need libraries or visits to places. You need to survey the scene. Walk the landscape. Test your ideas, check your facts. You need to overhear that conversation on the bus that makes you think, Ah, yes… You need that supper with friends that somehow nudges you over a sticky plot point, even without a word spoken about the blockage. In short, you almost certainly need stimulation beyond the recesses of your own brain.

The creative process is an extraordinary one. Sometimes it’s plodding. Often it’s frustrating. On good days you sit down to write and the story flows. Ideas you didn’t know you’d been thinking about pour onto the page. Hooray for the subconscious mind which works away at a story when you think you’re off duty. Walking, talking, sleeping even. If I’ve learned anything over the course of writing my three published novels it’s that I need to write a plan, to show up at the page and then just get on with it. Without worrying too much.

I recently heard the handbag designer Anya Hindmarch talking on the radio about her creative process. ‘It’s quite difficult with all the museums and exhibitions shut at the moment,’ she said. ‘I need to keep things going in.’ Her solution? She ‘banks’ ideas when she gets the chance, and goes back and ‘grazes’ on them later.

That was a lightbulb moment for me. I suddenly realised why the pandemic has been such hard work for me as a writer. Yes, some of us have the unaccustomed luxury of time. But let’s face it, life under lockdown has been pretty boring, even setting aside for a moment what a wise friend of mine calls the ‘ambient anxiety’ brought on by the pandemic. You’ve probably noticed in your conversations with friends. We haven’t got anything to bring to the table because none of us has done anything very interesting.

‘Surrounding myself with images I find interesting or inspiring subconsciously prompts ideas,’ said Anya Hindmarch. ‘That and a glass of wine. It relaxes me and the creative juices begin to flow.’

So yes, I’ve written a novel during the pandemic. Or finished and edited one that I’d already started. Joy and Felicity is officially launched. I haven’t started anything else concrete, although I’ll confess to playing with some early ideas for what may turn into my next book. Nor have I made ten types of sourdough, taken over an allotment or improved my French. But I refuse to beat myself up about that. Sometimes simply keeping afloat is enough of an achievement.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed